I don’t often see art that makes me weepy. I might be sensitive, but I’m not that sensitive.

But one recent summer night as I stood in a crowded gallery room in The Broad museum, surrounded by Angelenos and people of many races, ages and genders, tears welled in my eyes.

I was there to see an extraordinary exhibition: Jeffrey Gibson: the space in which to place me. The name of the show is borrowed from a poem by Oglala Lakota poet Layli Long Soldier about identity.

Born in 1972, Gibson is a member of the Mississippi Band of Choctaw Indians and of Cherokee descent. In 2024, he was the first Indigenous artist to represent the United States with a solo exhibition at the Venice Biennale. This show is his first at The Broad. And it’s one, if you’re in Los Angeles this summer, you should hurry to see before it closes.

Gibson’s ancestors originally lived in the Southeastern United States, in what is now Mississippi, before they were forced out of their homelands by the federal government to walk to Oklahoma. Many died along the way. It was winter; there was little food. And so the march came to be called the Trail of Tears. My Chickasaw ancestors were on that walk, too. Maybe you read a sentence or two about it in your high school history book? It’s a dark, shameful time in America’s history, but that’s the point.

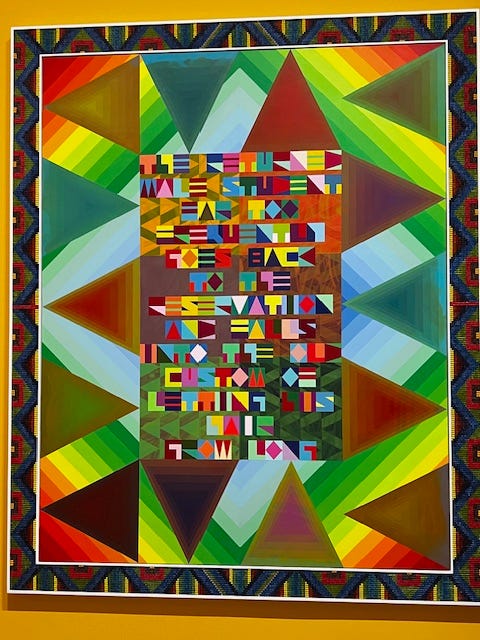

This is what makes Gibson’s arresting work not only powerful but relevant today, as the government bans books, blithely shutters DEI programs and deports immigrants. Using an array of mediums Gibson explores Native American identity, stereotypes and history. There are ceramic heads fashioned of colorful glass beads that could be women or men, reflecting Mississippian effigy pots, a tradition of Gibson’s ancestors. There are soaring figures made of beads, ribbon, fringe, and tin jingles reflecting powwow regalia. There are vibrantly colored murals, where if you stand back and look at the intricate geometric patterns long enough, you’ll discover a string of text. Taken from real documents and letters, they are cries for freedom, nods to resilience and healing, and expressions of joy.

Behind Gibson’s work lies a question: Who is democracy for?

The painting that particularly struck me was subtly embedded with these words: THE RETURNED MALE STUDENT FAR TOO FREQUENTLY GOES BACK TO THE RESERVATION AND FALLS IN TO THE OLD CUSTOM OF LETTING HIS HAIR GROW LONG. This is a direct quote from a letter written in 1902 by the Commissioner of Indian Affairs. It was addressed to a school superintendent in Central California, a scold of sorts about the importance of Native school children cutting their hair and conforming to Eurocentric-style ways of dress.

So come see Jeffrey Gibson’s astonishing show. There’s also a bedazzling video installation by Sarah Ortegon HighWalking, who is of Eastern Shoshone and Northern Arapaho descent. It shows her in a nine-channel video doing a traditional Jingle Dance to the music of the Halluci Nation, a First Nations Electronic Music Group. The Jingle Dance is a treasured ceremonial dance performed by women on the powwow circuit, but until recently it was banned for decades.

In case you’re wondering, I thought I should mention that downtown LA, where the Broad is situated on Grand Avenue near glorious Disney Hall, is under control. The Pentagon just sent 2000 National Guard troops home and pulled out 700 Marines. So we’re all safe again.